Vipul Singh

Given the abundance of varied water bodies and the socio-economic importance of fisheries in Bihar, a Commons-Based Fisheries Management Model offers a balanced, sustainable, and community-driven approach. This model supports both ecological integrity and fishing community’s livelihood.

Introduction

Inland fisheries have long remained on the margins of historical inquiry, overshadowed by grand narratives of agriculture, empire, and industrial development. This neglect is partly due to the scarcity of primary records and systematic data, which has posed significant challenges to researchers. However, in recent years, this silence is being increasingly questioned. As environmental history expands its scope, specially with the advent of the ‘animal turn’ that brings non-human actors into sharper focus, historians have begun to revisit the role of inland aquatic systems in shaping livelihoods, ecosystems, and regional economies. This emerging interest marks a significant shift in how we understand human-nature interactions in the past, revealing that inland fisheries are not peripheral, but integral to the broader environmental and social history of many regions.

To what extent did the colonial state’s fiscal imperatives shape the legal reconfiguration of riverine fisheries? This question prompts a critical examination of how revenue-driven governance transformed access to aquatic resources, often at the expense of customary fishing rights that had endured for centuries. In tracing this transition from community-based practices to state-controlled management, we encounter a deeper concern: What were the socio-cultural consequences for communities whose identities, livelihoods, and diets were intricately tied to riverine ecologies?

This article explores how colonial interventions disrupted these long-standing relationships by recasting rivers as sources of extractive value rather than shared commons. It argues that such legal and institutional changes not only altered ecological governance but also eroded the cultural and subsistence foundations of many fishing communities. Drawing on this historical critique, the article concludes by proposing a model for the sustainable growth of inland fisheries – one that reaffirms ecological balance and community knowledge within the framework of contemporary resource management.

The archival sources of court cases related to inland fisheries tells us that in many of the judgments there was a gradual shift in the colonial judiciary’s stance, from early rulings that supported public fishing rights to later decisions favouring private claims. These judgements aligned with government revenue goals at the expense of fishers community rights. The livelihood of the fishers community remained pathetic and they were relegated to working as daily wagers. So the bottom line is, can we make the lives of the vulnerable fisher community viable? This question challenges us to rethink leasing out systems and explore sustainable models that ensure equitable access to resources, improve livelihoods, and empower fishers. By addressing historical inequities and introducing inclusive, community-based governance, we can create opportunities that offer long-term economic stability and dignity for the fisher community.

The Commons-Based Management Model builds on the historical insights that we get from the heavily rich water resource state of Bihar. The model basically advocates for community-led management, legal protections for public access, and cooperative resource as a sustainable alternative. This model prioritises ecological sustainability, equitable resource distribution, and the preservation of fishers’ cultural heritage tied to riverine waterscapes. So, by leveraging lessons from the past, we are better positioned to enrich contemporary discussions on the governance of inland fisheries.

Was the European model viable in Bihar?

Bihar is blessed with an abundance of rivers and waterbodies, nourished annually by generous monsoon rains. During the colonial period, officials transformed various water bodies, apart from major rivers, into private property under the Permanent Settlement system. However, for several decades after the implementation of the Permanent Settlement, fishermen continued to fish in seasonal water bodies and ponds based on traditional rights. The scope for fishing further narrowed after the introduction of Alluvion and Diluvion Regulation (ADR) in 1825. By the mid-19th century, colonial authorities realized that fish production from seasonal water bodies and ponds, in addition to rivers, could also generate tax revenue.

Simultaneously, landlords began to recognize the economic benefits of fish production, leading to conflicts between fishermen and landlords over fishing rights. These conflicts prompted the government to enact the Fisheries Act of 1889, which sought to define ownership of fishing rights in private water bodies. By the Bengal Private Protection Fisheries Act of 1889, it was clearly notified that taking fish from a river or even from ‘enclosed piece of water’ would be an offence under the penal code (BPPFA 1889, p. 104). This legislation effectively eroded the traditional fishing rights of fishermen. Fishing in someone else’s jurisdiction was now classified as a cognizable offense. Consequently, longstanding disputes arose between landlords and fishermen over traditional fishing rights in ponds where fishermen had fished for generations. In 1872, A.R. Mangles, the Collector of Patna, wrote in a letter [Letter from A.R. Mangles, Esq., Collector of Patna, to the Offg. Commissioner of the Patna Division, No. 343, 1872, Bankipore, in Pros. No. 20, Land Revenue Department, November 1872, West Bengal State Archive] that fishermen’s traditional rights to fish in ponds and tanks had been established over many years. Many of these disputes escalated to court cases.

This colonial effort to organize fish production across all water bodies reflected European influence. The government aimed to manage fish production in water-rich regions like Bihar and Bengal, as was done in Europe, to increase fish production and government revenue. However, the colonial administration failed to grasp the unique nature of Bihar’s water systems. Unlike in Europe, seasonal water bodies like ponds, lakes, and tanks in Bihar often connected to major rivers during the monsoon months from June to October.

In 1895, A. Forbes, another Collector of Patna, highlighted this issue in a letter to the government, emphasizing that when these water bodies merged with rivers, the ownership of fishing rights became ambiguous. In his letter, he advocated for fishermen’s rights to fish in seasonal water bodies. As a result, fishermen and malah communities were granted the right to fish in seasonal water bodies, ponds, and tanks. The Inland Fisheries Act of 1897, covering the whole of India, was passed based on the experiences of Bengal PrivateProtection Fisheries Acts 1889.

Effect on Fishing Community

The erection of embankments, construction of highways and railways had already been affecting the flow as well as the course of the rivers. The rivers were obstructed from flowing freely and so flood became unruly. It led to the inundation of the homestead of the fishing communities, who lived mostly in the diara lands. They preferred to migrate temporarily during the flood months. Most of the homestead in diara was on a mound and in the pre-colonial period the communities often remained in their villages living on the storage done during November to June every year. During the flood months they were able to sell fishes in the urban areas. Free nature fishes were most important in floods times because flood had destructive nature. Flood could be destructive to the main food resource and the economic basis of people. In this situation free nature of fisheries had played the most important role in sustaining people’s livelihoods. During flood months, free fishes fulfilled protein requirement of the local landless fisher communities.

The scenario changed drastically after the British regulations on such commons. Thereafter, the landless communities living in the diara villages, particularly the fishers did not have enough food to survive the inundation months. Resultantly, they preferred to migrate to theneighbouring urban areas during the months of July to November. Most of them migrated every years in search of work and food. Over the years, the phenomena of temporary migration of many diara villagers became permanent in nature as fish catching from the rivers and streams, their main livelihood, had become illegal.

Commons-Based Fisheries Management Model

After independence, the Inland Fisheries Acts of 1897 remained the basis for the governance of inland fisheries. Historically, control over perennial waterbodies and diara waterfronts in Bihar was concentrated in the hands of large landholders. The government leased the lakes, ponds and rivers to the highest bidders, often excluding the fisher community from direct access to these resources. Instead, fishers were employed by leaseholders to catch fish, receiving only daily wages for their labor. This system marginalized the fisher community, rendering them the most vulnerable group in an environment abundant with aquatic resources.

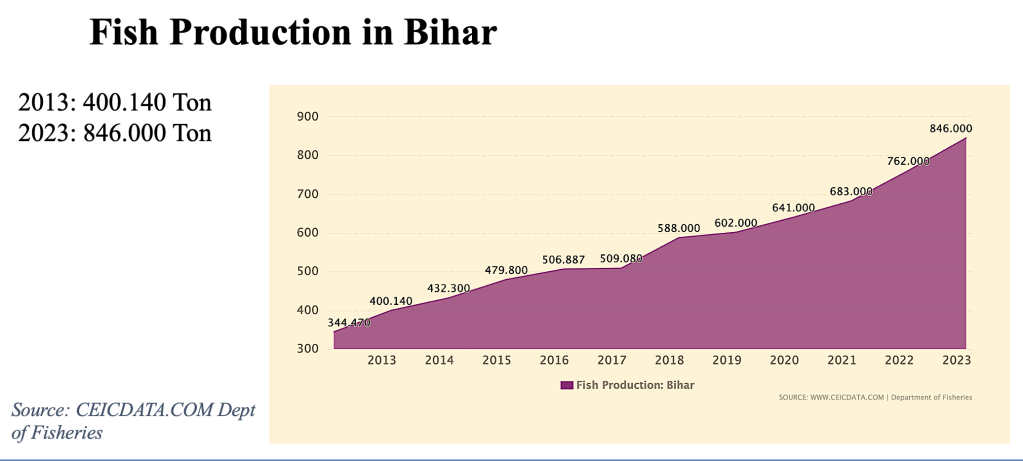

The historical insights that we get from the nineteenth century with Bihar as a case suggests that a commons-based management model (CBFM) best fits for such riverine regions. It advocates for community-led management, legal protections for public access, and cooperative resource stewardship as a sustainable alternative. This model prioritizes ecological sustainability, equitable resource distribution, and the preservation of cultural heritage tied to riverine waterscapes. In community-based management, local communities develop context-dependent solutions for matching exploitation rates to the productivity of local resources. Bihar is the perfect case of success story of this model, which has led to the persistent growth of fish production. In Bihar, fish production was reported at 846.000 Ton in 2023. It was 400.140 Ton in 2013.

East Champaran as a Case

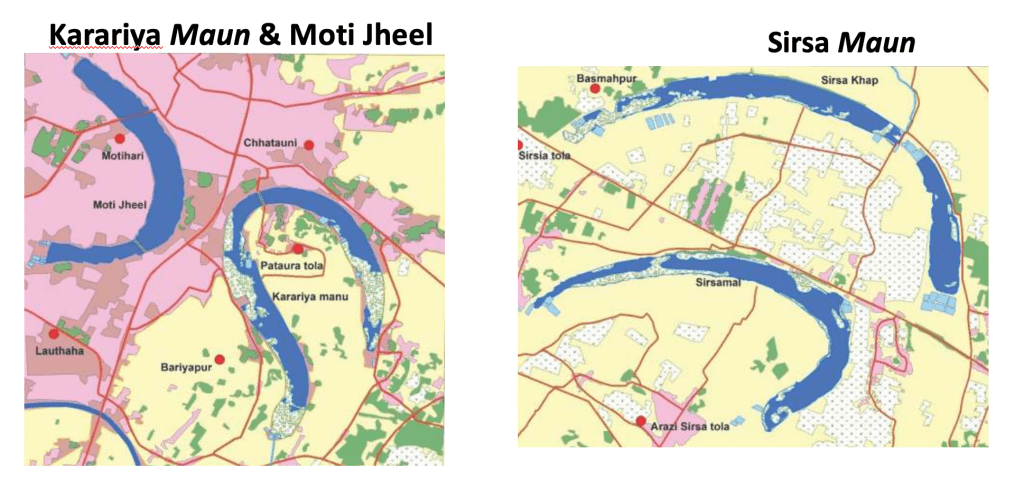

East Champaran has a large potential for fishery development. The district of East Champaran has the highest maximum, minimum and average perennial bodies (Water throughout the year) spread area. The district has quite a large number of rivers, lakes called maun, marshes, pond and tanks. Fisheries industry is one of the upcoming industry in East Champaran.

The yearly production of fish is estimated about 2500 M.T. of worth Rs. 25 crores. The common species found in the district are carps Rohu, Catla, Naini,Calvasu, Catefish, Boari, Tengra, Silonal, Bangas, Bachawa, Murels, Garai, Sawra, Chenga, Chitla, Hilsa, Gorarah,Pothiya, Chelwa, Bami, Gaineha, Changari,etc. The world Bank financed 19 crore rupees for fisheries development schemes in Moti Jheel and Kararia Jheel in Motihari town and its adjoining area to develop the maun (lakes) suitable for fish production.

The frequent floods and droughts in Bihar necessitate a participatory approach to resource governance. Community participation is crucial. Unlike the current state’s sovereign control over natural resources, medieval Bihar had individual and community ownership of water resources. The ruler’s land grants, which often included water bodies, didn’t imply monopolistic state ownership. This decentralisation allowed local communities to determine resource use and management rights.

Commons, such as seas, public lands, and forests, are large and contain natural or human-made resources. They have two distinct characteristics: excludability, the difficulty of controlling access, and subtractability, where each user can reduce the welfare of others when using the resource. Most commons are considered degradable, where each user can reduce the quantity or quality of the resource. In commons, rights are usually allocated to a specific group of users. Users are responsible for managing resources and may exclude others from sharing them.

In 2006, in a bold move the Bihar government passed the Bihar Fisheries Jalkar Management Act, 2006. It has not only ensured that the Department of Fisheries, Government of Bihar, has the ownership of the state’s open water bodies, but at the same time, traditional fishers are granted access to these water bodies under specified conditions and reasonable restrictions. Some waterbodies in Bihar are privately registered properties and remain under private ownership. But those owned by government have been brought under the ambit of the new Act. Fisheries management rights for government-owned mauns and diara are allocated to fishers, Fishermen Co-operative Societies, and fishers’ Self-Help Groups. These mauns and chaurs are leased to the highest bidder from the traditional fisher community, Fishermen Co-operative Societies, or Self-Help Groups for a lease period of 7 to 10 years. Traditional fishers and Fishermen Co-operative Societies also have rights to fish in rivers.

An amendment to the 2006 Act was introduced in 2018. Now the mauns and waterbodies are leased to the highest bidder from the traditional fisher community and their Fishermen Co-operative Societies, or Self-Help Groups for a maximum lease period of 5 years. They are typically leased for 3 to 5 years. The new clause also prohibits any Fishermen Co-operative Society from altering the settlement period with its members without the approval of the competent authority.

Conclusion

Given the abundance of varied water bodies and the socio-economic importance of fisheries in Bihar, a Commons-Based Fisheries Management Model offers a balanced, sustainable, and community-driven approach. We have many success stories from East Champaran mauns . This model supports both ecological integrity and fishing community’s livelihood. It also ensures that Bihar’s natural resources, particularly its abundance of perennial waterbodies are utilized effectively to bring prosperity, food security, and self-reliance to fishers.The Commons-Based Fisheries Management Model that has been implemented in the Fisheries Development of various Mauns of East Champaran and other waterbodies of Bihar. Wetland is highly viable for vulnerable fishers due to its emphasis on inclusivity, sustainability, and community empowerment. The income of fishers’ households has seen significant growth, with average household earnings from fisheries increasing by nearly 40%, reaching approximately ₹60,000. [Source: Policy Paper published by ICAR-CIFRI, 2019]. Technological interventions have been well-received by local fishers, as they have not only addressed unemployment but also contributed to reversing youth migration by providing local job opportunities.

References

BPPFA. (Bengal Private Protection Fisheries Acts (1889) Proceeding of Legislative Department, National Archives of India, New Delhi.

Cullet, P. and Gupta, J. (2009) Evolution of water law and policy in India. In: The Evolution of the Law and Politics of Water (eds. J.W. Dellapenna and J. Gupta), Springer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, pp.159-175. Available from http://www.ielrc.org/content/a0901.pdf. Accessed on 10 June 2016.

Day, F. (1873) Report on the Fresh Water Fish and Fisheries of India and Burma. Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing, Calcutta.

El-Hinnawi, E. (1985) Environmental Refugees. United Nations Environmental Programme, Nairobi, Kenya.

Hunter, W. (1876) A Statistical Account (vol-11). D.K. Pub. House, Delhi, pp. 30-35.

Hunter, W. (1877) A Statistical Account of Bengal (vol-20). Trubner & Co., London.

Government of Bengal (1888) Letter from the Secretary to the Government of India to the Chief Secretary to the Government of Bengal, Circular No. 54, dated 13th June, 1888, Legislative Department Proceedings, National Archives of India, New Delhi.

Government of Bengal (1889) Letter from Assistant Secretary to the Government of Bengal to the Secretary to the Government of India, No. 83, dated 19th March, 1889, Legislative Department Proceedings, National Archives of India, New Delhi.

McGinn, P. (2009) Capital, ‘development’ and canal irrigation in colonial India. Working paper. Institute for Social and Economic Change, Banglore. Available from http://www.isec.ac.in/WP-209.pdf. Accessed on 10 August 2015.

Nayak, P.K. and Berkes, F. (2011) Commonisation and decommonisation: understanding the processes of change in the Chilika Lagoon, India. Conservation and Society 9, 132-45.

Rajan, R. (1998) Imperial environmentalism and environmental imperialism: European forestry, colonial forester and the agenda of forest management in British India 1800-1900. In: Nature and the Orient (eds. R.H. Grove, V. Damodaran and S. Sangwan. Oxford University Press, New Delhi, pp. 359-360.11

Reeves, P. (1995) Inland waters and freshwater fisheries: issues of control, access and conservation in colonial India. In: Nature, Culture and Imperialism: Essays on the Environmental History of South Asia (eds. D. Arnold and R. Guha), Oxford University Press, Delhi, pp. 260-292.

Singh, V. (2012) Environmental migration as planned livelihood among the Rebaris of Western Rajasthan, India. Global Environment 9, 50-73.

Singh, V. (2017) “Where many rivers meet: river morphology and transformation of pre-modern river economy in Mid-Ganga Basin, India”. In: Environmental History in the Making, Vol. I: Explaining (eds. E. Vaz, C.J. de Melo and L.M.C. Pinto), Springer International Publishing, Switzerland, pp. 187-206.

Singh, V. (2018) Speaking River: Environmental History of A Mid-Ganga Flood Country, 1540-1885. Primus Book, Delhi.

Willcocks, W. (1930) Ancient System of Irrigation in Bengal and Its Application to Modern Problems. Reprinted in 1984. B. R. Publishing Corporation, Delhi.

- Doing Public History?

- Faculty Guidelines Handbook

- Commons-Based Fisheries Management Model: Success Story from Bihar

- Field Report : Alang-Sosiya Ship-breaking Yard

- Resources

Vipul Singh is an environmental historian and Professor at the Department of History, University of Delhi, Delhi. He is an alumnus Carson Fellow of the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society, Munich, Germany.

Leave a comment